On an early March afternoon in 1882, novelist Mark Twain paid a visit to the Wall Street office of his old friend, Ulysses S. Grant. The former president had retired to a quiet business life, but he still had political connections. In tow was another of Twain’s great friends, the literary critic William Dean Howells, who was hoping to enlist Grant’s aid on a small political matter.

Grant, and seventh from Samuel. Mathew Grant’s first wife died a few years after their settlement in Windsor, and he soon after mar-ried the widow Rockwell, who, with her first husband, had been fellow-passengers with him and his first wife, on the ship Mary and John, from Dorchester, England, in 1630. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; / ˈ h aɪ r ə m juː ˈ l ɪ s iː z / HAHY-rəm yoo-LIS-eez; April 27, 1822 – July 23, 1885) was an American military leader who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As president, Grant was an effective civil rights executive who created the Justice Department and worked with the Radical Republicans during. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Personal Memoirs of U. Grant, Complete Author: Ulysses S. Grant Release Date: June 1, 2004 EBook #4367 Last Updated: June 20, 2018 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1.

Over a lunch of baked beans, bacon, and coffee, the three men quickly took care of business, and the remaining conversation centered on personal matters. Twain, ever fascinated by Grant’s stories, tossed a suggestion on the table: Grant should write some of those stories down in a memoir.

Grant demurred. He had no interest in revisiting his past. Anything he had to say had already been included in a three-volume Military History of Ulysses S. Grant written by his former aide, Brigadier General Adam Badeau, with Grant’s full cooperation. “It is all in Badeau,” Grant told another would-be literary suitor, putting a preemptory end to all memoir discussions. [1]

“[Grant] had no confidence in his ability to write well,” Twain later explained, “whereas I and everybody else in the world excepting himself are aware that he possesses an admirable literary gift and style.” Grant’s insights were also unique. “[W]hat another man might tell about General Grant was nothing, while what General Grant should tell about himself with his own pen was a totally different thing,” [2]

But in May 1884, circumstances in Grant’s life changed dramatically, forcing him to reconsider his decision. On Sunday, May 4, one of Grant’s business partners showed up on the front stoop of his Manhattan townhouse with bad news; their investment firm, Grant & Ward, faced financial trouble. Could Grant come up with $150,000, he asked, to keep the company solvent until the banks opened on Monday?

The partner, 30-year-old Ferdinand Ward, was known as “the Young Napoleon of Wall Street” because of his financial genius; his investors earned returns as high as 40 percent. [3] “I had the greatest confidence in him and I consider him to be a very able man,” said another of the firm’s partners, Grant’s second-oldest son, Ulysses S., Jr., also known as “Buck.” [4]

While Ward contributed his financial wizardry to the firm, Grant contributed the tremendous prestige of his name. “I am willing that Mr. Ward should derive what profit he can for the firm that the use of my name and influence may bring,” Grant once said. [5] A fourth partner, James Fish, president of the Marine Bank, lent his own financial reputation to the firm as one of the great lions of Wall Street.

Grant quickly secured a $150,000 loan from his friend, William Henry Vanderbilt, reportedly the richest man in America. The loan would keep the firm afloat until Ward could get things sorted out with the banks when they reopened on Monday.

Unbeknownst to either of the Grants, Ward had been using the firm to run an elaborate Ponzi scheme—collecting money from investors that he would then use to pay off earlier investors while pocketing a large percentage of the money for himself.

Despite Vanderbilt’s check, Ward’s house of cards collapsed just two days later, on Tuesday, May 6. It would take several days for investigators to uncover the scale of Ward’s fraud; with Fish’s help, he had fleeced investors out of nearly $16.8 million. Among the victims were the entire Grant family. [6] Aside from $80 stuffed in Grant’s pocket and another $130 his wife, Julia, had stashed in a cookie jar, the swindle had left the Grants destitute. “Imagine the shock to us, who thought we were independently wealthy!” Julia later said. [7]

The collapse of Grant & Ward and the bankruptcy of its most famous partner made national news. Friends offered help, but Grant, too proud to accept charity, refused. Several others stepped up with “loans,” which Grant felt better about accepting—fully intending to repay each one. The first such loan came from Charles Wood of Lansingburgh, New York. “[M]y share due for services ending about April 1865,” Wood wrote. [8] Such generosity bought Grant and his family enough time for them to sell a number of properties they owned, thus securing enough resources to stay afloat.

As word of Grant’s financial misfortune spread, the editors of The CenturyIllustrated Monthly Magazine decided the time might be right to approach Grant about doing some writing. The Century had approached Grant once already but, like other literary suitors, had been rebuffed. Editors wondered now whether Grant, with his finances in shambles, might reconsider. They even employed Adam Badeau to help enlist Grant’s participation.

Grant agreed, and associate editor Robert Underwood Johnson met with Grant to finalize details: The Century would pay $500 each for articles on Shiloh, Vicksburg, the Wilderness, and Chattanooga. [9] Grant accepted. “[H]e gave me the impression of a wounded lion . . .” Johnson later recounted of his visit. “I left him with a deep impression of his dignified sorrow, his courage, and his greatness.” [10]

Grant’s first draft read like a dry official report, but under additional guidance from Johnson, subsequent drafts improved dramatically. “[N]o one ever had an apter pupil,” Johnson later wrote. [11] Grant sought additional help from Badeau. As the writing continued, and eventually took on a life of its own, Badeau moved into the Grants’ townhouse so he could be on hand to assist.

The more Grant wrote, the more he loved writing. “He got out of the writing not only diversion from his troubles but the happiness of finding that he could do something new,” Johnson observed. “He said to me once: ‘Why, I am positively enjoying the work. I am keeping at it every day and night, and Sundays.’” [12]

In fact, Grant was well practiced with the pen—a realization he would eventually come to after months of work. “I have to say that for the last twenty-four years I have been very much employed in writing,” he later confessed.

As a soldier I wrote my own orders, plans of battle, instructions and reports. They were not edited, nor was assistance rendered. As president, I wrote every official document, I believe, usual for presidents to write, bearing my name. All these have been published and widely circulated. The public has become accustomed to my style of writing. They know that it is not even an attempt to imitate either a literary or classical style; that it is just what it is and nothing else. If I succeed in telling my story so that others can see as I do what I attempt to show, I will be satisfied. The reader must also be satisfied, for he knows from the beginning what to expect. [13]

And so the work progressed. As Julia recalled, “All that summer was spent by my dear husband in hard work: writing, writing, writing for bread.” [14]

By the end of summer, Grant realized he was onto something larger. “I do not think I care to write any more articles, for publication, than I have already agreed to write for the Century,” he informed Johnson. [15] Instead, he set his sights on a far more ambitious project. “I intend . . . now that I have commensed (sic) to it, to go on and finish all my connection with the war of the rebellion whether I publish it or not,” Grant wrote a friend. “If it pleases me when completed I probably will publish it.” [16]

Everyone involved knew the sales potential of such a memoir. “Do you really think anyone would be interested in a book by me?” Grant asked the editors of The Century, somewhat coyly. [17] After more conversation, they soon came to an understanding that The Century would handle the book’s publication.

Mark Twain, in town for business, heard of the ongoing negotiations. He, too, recognized the sales potential. “[H]ere was a book that was morally bound to sell several hundred thousand copies in its first year of publication,” he knew. [18] Nor had Twain forgotten his earlier attempt to get Grant to write his memoirs—so he stopped by Grant’s to see what he might discover.

“Sit down and keep quiet until I sign a contract,” Grant told his friend, inviting Twain to take a seat as Grant studied a written offer from The Century.

“Don’t sign it,” Twain said, asking Grant’s son, Fred, to read it aloud to him first. Twain reminded them that he’d had “a long and painful experience in book making and publishing,” so his advice on the contract might be useful. [19]

The three of them began discussing alternatives to The Century’s offer. Grant, at first, didn’t budge, feeling as though he owed the book to The Century because they had approached him first. “In that case,” Twain replied, “I’m to be the publisher because I came to you first.” [20]

This gave Grant pause. Finally, he agreed to consider Twain’s offer. For nearly three months, Grant sought the opinion of several trusted confidents—none of whom had any stake in the venture whatsoever—and finally concluded that Twain, indeed, offered the best deal. Twain’s publishing company, Charles Webster & Co., would give Grant 75 percent of the net returns and assign all the rights to Julia as a way to protect those proceeds from Grant’s creditors.

The months of negotiations, and the months of writing, suggest an upswing in Grant’s fortunes. However, other events simmering in the background since early June began to force their way to the forefront. “It was during this sad summer,” Julia later said, “that the fatal malady first made its appearance.” [21]

Spotting “a plate of delicious peaches on the table,” Grant helped himself, Julia recalled. “[T]hen he started up as if in great pain and exclaimed: ‘Oh my, I think something has stung me from that peach.’ He walked up and down the room . . . and rinsed his throat again and again. He was in great pain and said water hurt like fire.” [22]

For weeks, Grant brushed off the discomfort, which nagged at him. Instead, he focused on his writing. “I work about four hours a day, six days a week, on my book,” Grant wrote to his former subordinate, William T. Sherman, in mid-October. “My [first] idea was that it would be a volume of from four to five hundred pages. But it looks now as if it will be two volumes of nearly that number of pages each.” [23]

Around that time, Grant finally sought an appointment with his doctor—who was so alarmed by what he saw that he immediately sought additional opinions. The unanimous diagnosis: throat cancer. “General, the disease is serious,” one of the doctors told him. Privately, another offered a far grimmer pronouncement, “General Grant is doomed.” [24]

Through the rest of the fall and into the winter, Grant soldiered on—at first not even telling his family about the diagnosis. He would write, then pass the pages on to Badeau and Fred, who would fact-check. Periodically, bouts of depression brought writing to a standstill, though, and flare-ups of pain likewise stopped work. “He had no care to write, not even to talk; he made little physical effort, and often sat for hours propped up in his chair, with his hands clasped, looking at the blank wall before him, silent, contemplating the future; not alarmed, but solemn, at the prospect of pain and disease, and only death at the end.” [25]

Each time, Grant rallied. He survived a nearly crippling bout of despondency in December; a stressful deposition against Ward and Fish in March; and an almost total collapse of his health in late March. “All this while, the public interest was painful,” Badeau reported. “So much of it penetrated into that house under the shadow of Death, that it seemed to us within as if the whole world was partaking of our sorrow.” [26]

However, April brought with it a series of public commemorations in April that buoyed him even more: the twentieth anniversary of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Easter, his birthday. Thousands of letters and cards streamed in. “Down in my heart,” Julia later wrote, “I could not believe that God in his wisdom and mercy would take this great, wise, good man from us, to whom he was so necessary and so beloved. It could not be, and I surely thought he would recover.” [27]

Grant’s friends and admirers also did what they could to secure his financial situation. Sherman tried to raise money from several wealthy benefactors, although Grant called off the effort as soon as he got wind of it. Showman P.T. Barnum offered to send an exhibit of Grant’s personal effects on a round-the-country tour to raise money, but Grant demurred because he worried the artifacts belonged to creditors. Vanderbilt tried to forgive the loan he’d made to Grant, but Grant refused, going so far as to take Vanderbilt to court to force Vanderbilt to enforce the loan.

In March, bi-partisan supporters in Congress pushed to reinstitute Grant’s military pension, which he had forfeited to become president. By law, the legislation had to pass before the new president was sworn in at noon on Inauguration Day. Political rancor on another matter deadlocked the bill even as the hour hand neared twelve. The impasse broke, and Senate leaders moved their clock back by twenty minutes in order to give themselves enough time to approve the pension. President-elect Grover Cleveland took his oath of office twenty minutes late, and as one of the first acts of his presidency, authorized the pension to take effect.

Then came perhaps the worst personal blow of the whole up-and-down ordeal; Adam Badeau tried to blackmail Grant. Press reports erroneously suggested that Badeau, not Grant, was the principal author of the memoirs. Instead of contradicting those reports, Badeau demanded more money from Grant and, in exchange, promised to “declare as I have always done that you wrote it absolutely.” [28] Rather than succumb, Grant kicked Badeau out. Having been betrayed by Ferdinand Ward, the general was not about to stand for another such turn. “[M]y book would never have been finished as ‘my book’ if you had been permitted to continue in the capacity you now seem disposed to think you were in,” Grant wrote to Badeau later. “I however never regarded you in any such capacity.” [29]

As the spring of 1885 wore on, visitors came and went. “His mind was absorbed with the one subject of his military autobiography and a desire to be accurate in the most minute particulars,” former subordinate James Wilson wrote. “In all matters aside from his book, Grant took but a slight and passing interest.” [30]

But even as the writing continued, Grant’s health weakened. “The fact is that I am a verb instead of a personal pronoun,” Grant would eventually observe. “A verb is any thing that signifies to be, to do, or to suffer. I signify all three.” [31]

By mid-June, doctors relocated Grant from midtown Manhattan to a mountaintop resort north of Albany, the Balmoral Hotel located atop Mount McGregor. The milder climate would ease his discomfort and, they hoped, prolong his life. To preserve his strength, Grant gave up speaking and conversed through slips of paper on which he would scratch notes with a pencil.

“There is much more that I could do if I was a well man,” Grant wrote Twain on June 29. “I do not write quite as clearly as I could if well. If I could read it over myself many little matters of anecdote and incident would suggest themselves to me.” [32]

“I would have more hope of satisfying the expectation of the public if I could have allowed myself more time,” he wrote in the preface of his book. “Man proposes and God disposes.” [33]

Many more visitors made the trek up the mountain to pay their last respects to the dying hero. Among them was Charles Wood, whose first “loan” saved Grant from ruin. Grant had repaid Wood from the proceeds of his first Century article; Wood, in turn, had donated the money to charity. “I feel very thankful to you for the kindness you did me last summer,” Grant wrote in his “pencil talk.” “I am glad to say that while there is much unblushing wickedness in this world yet there is a compensating generosity and grandeur of soul.” [34]

Robert Underwood Johnson likewise paid a visit. “The General, fully dressed, sat on the piazza in the sun, wearing something over his head, like a skullcap, and wrapped in a plaid shawl, looking thinner than before, and with a patient, resigned expression, but not with a stricken look,” Johnson recalled. “I could hardly keep back the tears as I made my farewell to the great soldier who had saved the Union for all its people, and to the man of warm and courageous heart who had fought his last battle for those he so tenderly loved.” [35]

All the while, Grant “was sinking fast and suffering intensely,” one observer noted. Still he worked, still he wrote. [36] “I am sure I will never leave Mt. McGregor alive,” he finally confessed to Julia. “I pray God however that [I] may be spared to complete the necessary work upon my book.” [37]

Finally, on July 20—after eleven months, two volumes, 1,231 pages, and 291,000 words—Grant finished. “[H]e put aside his pencil and said there was nothing more to do,” Twain recounted. [38]

Almost immediately, the dissolution Grant had held at bay began to take hold, and over the next two days, his condition deteriorated precipitously. On the morning of Thursday, July 23, 1885, doctors roused family members to gather around Grant’s bedside. “The outer air, gently moving, swayed the curtains at an east window,” TheNew York Times recounted. [39]

Into the crevice crept a white ray from the sun. It reached across the room like a rod and lighted a picture of Lincoln over the deathbed. . . . The light on the portrait of Lincoln was still sinking; presently the General opened his eyes and glanced about him, looking into the faces of all. The glance lingered as it met the tender gaze of his companion. A startled, wavering motion at the throat, a few quiet gasps, a sigh, and the appearance of falling into a gentle sleep followed. . . . He lay without motion. At that instant the window curtain swayed back in place, shutting out the sunbeam. [40]

Fred Grant stopped the clock that sat on the fireplace mantel at 8:08 a.m. Ulysses S. Grant had beaten his deadline by three days.

The first of Grant’s Century articles, “The Battle of Shiloh,” eventually appeared in the magazine’s February 1885 issue, immediately boosting its circulation. “Vicksburg” appeared in the September 1885 issue, “Chattanooga” in the November 1885 issue, and “Preparing for the Wilderness Campaign” in February 1886.[41]

The Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant appeared in two volumes, the first of which came out in December. In its first two years alone, it earned $450,000 in royalties, and since its initial publication, the book has never been out of print. [42]

“General Grant’s book is a great, unique and unapproachable literary masterpiece,” said Twain. “There is no higher literature than these modest, simple Memoirs.”[43] Sherman predicted the book would be the definitive account of the war—just as Grant hoped. “Other books of the war will be forgotten, mislaid, dismissed. Millions will read Grant’s Memoirs and remember them.”[44]

Grant did not want readers to forget that the late war had been about treason against the government. However, he dedicated his memoirs to “the American soldier and sailor”—both Northern and Southern. “The troops engaged on both sides are yet living,” Grant explained to Fred, who questioned the dedication. “As it is the dedication is to those we fought against as well as those we fought with. It may serve a purpose in restoring harmony.”[45]

This was Grant’s final vision—an extension of his famous words “Let there be peace.” [46] “The Confederate soldier vied with the Union soldier in sounding my praise,” he told Fred during those last weeks. “It looks as if my sickness had had something to do to bring harmony between the sections. . . . Apparently I have accomplished more while dying than it falls to the lot of most men to be able to do.” [47]

- [1] Adam Badeau, Military History of Ulysses S. Grant: from April, 1861, to April, 1865, 3 vols. (New York: D. Appleton, 1881); Robert Underwood Johnson, Remembered Yesterdays (Boston: Little Brown, 1923), 209.

- [2] Mark Twain, The Autobiography of Mark Twain, 3 vols., University of California Press 2001 ed. (New York and London: Harper and Brothers, 1924), 1:71.

- [3] Ward’s descendant, historian Geoffrey C. Ward—best known for his collaborations with filmmaker Ken Burns—wrote a fascinating biography of his infamous ancestor, A Disposition to be Rich (New York: Random House, 2012).

- [4] John Y. Simon, ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009), 144.

- [5] New York Tribune, May 27, 1884.

- [6] Investigators absolved Grant and Buck of any wrongdoing, but Ward and Fish were both convicted of fraud. Ward served six years in prison; Fish served four.

- [7] Julia Dent Grant, The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant (Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant), ed. John Y. Simon (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1975), 328.

- [8] Simon, Papers, 146-7.

- [9] Originally Grant agreed to write about Appomattox but later asked to swap it out for an article on Chattanooga. One of Johnson’s exasperated colleagues wrote, “Isn’t Lee’s surrender of most importance to us?” (Grant, 187)

- [10] Robert Underwood Johnson, Remembered Yesterdays (Boston: Little Brown, 1923), 210-13.

- [11] Johnson, Remembered Yesterdays, 215.

- [12] Ibid.

- [13] Simon, Papers, 355-6; “The last two sentences of this paragraph add up to excellent advice for any budding writer,” points out historian Bruce Catton in “U.S. Grant: Man of Letters,” American Heritage, 19, No. 4 (June 1968):98.

- [14] Julia Grant, Personal Memoirs, 329.

- [15] Simon, Papers, 187.

- [16] Ibid., 186.

- [17] Johnson, Remembered Yesterdays, 217.

- [18] Twain, Autobiography, 78.

- [19] Ibid.

- [20] Ibid.

- [21] Julia Grant, Personal Memoirs, 328.

- [22] Ibid.

- [23] Simon, Papers, 228.

- [24] John Douglas, 'Records of the Last Days of the Magnanimous Soldier U. S. Grant.” John Hancock Douglas Papers, Library of Congress. Portions of Douglas’s papers are excerpted as an appendix in Thomas M. Pitkin’s The Captain Departs: Ulysses S. Grant’s Last Campaign, Southern Illinois University Press, 1973.

- [25] Badeau, Military History, 428.

- [26] Adam Badeau, “The Last Days of General Grant,” in Grant in Peace: From Appomattox to Mt. McGregor, A Personal Memoir (Hartford, CT: S. S. Scranton, 1887), 452.

- [27] Julia Grant, Personal Memoirs, 329.

- [28] Simon, Papers, 347.

- [29]Ibid., 429-31.

- [30] James Grant Wilson, General Grant (New York: Appleton & Co., 1897), 354.

- [31] Simon, Papers, 441.

- [32]Ibid., 390.

- [33] Ulysses S. Grant, Memoirs and Selected Letters: The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, Selected Letters 1839-1865 (New York: Library of America, 1990), 5.

- [34] Simon, Papers, 419.

- [35] Johnson, Remembered Yesterdays. 223.

- [36] Noble E. Dawson, “Grant’s Last Stand.” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 6, 1894.

- [37] Simon, Papers, 416.

- [38] Mark Twain to Henry Ward Beecher in The Selected Letters of Mark Twain, ed. Charles, Neider, (New York: Harpers, 1982),cited from http://www.granthomepage.com/inttwain.htm, accessed December 9, 2015.

- [39]New York Times, July 24, 1885.

- [40] Ibid.,

- [41] In acknowledgement of the articles’ success, the Century increased the fee it paid Grant from the original $500 to $4,000 per article. Later, acting on behalf of Grant in the capacity of a literary agent of sorts, Mark Twain would claim to have played a role in increasing Grant’s stipend. “[I]t had never seemed to occur to [The Century] that to offer General Grant $500 for a magazine article was not only the monumental insult of the nineteenth century but of all centuries,” Twain wrote (Twain, Autobiography, 77). Later, he observed, “This was altogether the sharpest trade I have ever heard of, in any line of business, horse trading included” (Twain, Autobiography, 92). In Johnson’s memoir, however, he matter-of-factly recounts “a voluntary additional payment” (Johnson, Remembered Yesterdays, 219).

- [42] Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, 2 vols. (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1885-1886).

- [43] Twain, Autobiography, 2:71-72.

- [44] Sherman quoted by The Ulysses S. Grant Homepage: http://www.granthomepage.com/grantauthor.htm, Accessed December 9, 2015.

- [45] Simon, Papers, 410.

- [46] Grant used the phrase “Let us have peace” during his speech accepting the 1868 Republican presidential nomination, and it quickly became his campaign slogan. The phrase was subsequently carved above the entrance to his tomb in New York City.

- [47] Simon, Papers, 393.

The sick, aging warrior put down his pen. It was July 18, 1885, and Ulysses S. Grant had just finished his memoirs. The hero of war had no way of knowing his final determined act would also make him a literary hero. In terrible pain from throat cancer, hour after hour and day after day he had pushed himself to write his recollections from his cottage atop New York’s Mount McGregor. He knew the end was near. “Man proposes and God disposes,” he wrote. “There are but few important events in the affairs of men brought about by their own choice.”

Grant wrote the memoir in part because he had lost all his money in a financial scandal and hoped the sales of the book would provide income for his wife, Julia, and their children. But the general and president also wanted the world to know his thoughts about the Civil War and his role in the conflict. The result of his death-defying determination was the creation of one of the greatest pieces of nonfiction in all of American literature, a memoir that dozens of historians have used as a source to produce studies of the war, and that uncounted people have read for personal enrichment. The publication of such a work would have been extraordinary even if it had been accomplished by a completely healthy man, much less one who was deathly ill.

Near the end: Ever curious about world events, Ulysses S. Grant takes a short break from writing his memoirs to read the newspaper on the porch of his cottage atop New York’s Mount McGregor. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The contemporary readers of Grant’s memoirs had no problem understanding what he was saying and recognized the names mentioned in the book. After all, in the mid-1880s, the United States was still populated by people who had experienced the war. Most of the war’s veterans were about 40 years old, and their wives and families were similarly young. But in 2018, of course, all Civil War veterans are long gone, and the average reader has limited knowledge about what Grant was describing. Therefore, a modern version, edited to explain the details, was absolutely essential if this classic was to remain understandable to a wide audience. It was to that end that I, ably assisted by David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo, began work on an annotated version of The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant.

It was very important that the editors allow Grant to speak his mind and allow him, unencumbered, to express what he believed. After all, the memoirs emphasize Grant’s perspective. He said as much in his preface, “The comments are my own, and show how I saw the matters treated of whether others saw them in the same light or not.”

As the editorial team worked on the memoirs, certain passages stood out as emblematic of Grant’s personality and his blunt nature when it came to expressing his opinion. The determination he conveyed during the Civil War was evident during an instance when he described having to swim a swollen creek on horseback to be sure he proposed to his fiancée, Julia Dent, before he left for the Mexican War. After recalling the incident, he ruminated, “One of my superstitions had always been when I started to go anywhere, or to do anything, not to turn back, or stop until the thing intended was accomplished.” What an insight into Grant’s role in the Civil War and in the writing of his memoirs.

Nor did Grant hold back on political opinions, stating exactly what he believed. For example, regarding the Mexican War of 1846-48, in which he served as a junior officer just a few years past his West Point graduation, he wrote that “the occupation, separation and annexation, were, from the inception of the movement to its final consummation, a conspiracy to acquire territory out of which slave states might be formed for the American Union.”

Us Grant Memoirs First Edition

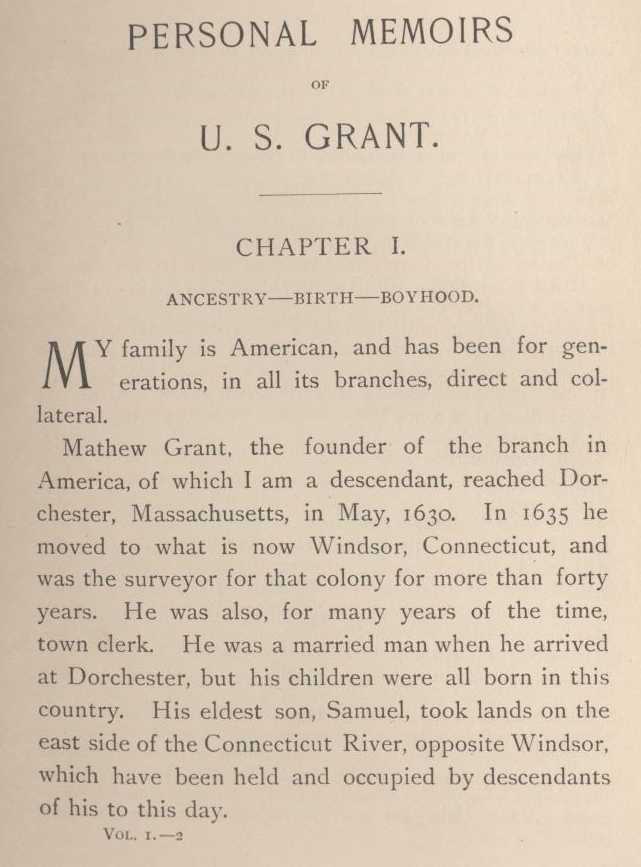

Stiff and New: Newly minted Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant poses in full military regalia in a ca. August 1861 image. Grant usually eschewed such finery, and related in his memoirs the taunting he received from a stable boy when he wore his uniform home after he left West Point. (CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

When it came to the Civil War, once again he saw slavery’s dire role: “The cause of the great War of the Rebellion against the United States will have to be attributed to slavery.” Despite believing that slavery, which he disliked, was the cause of the war, he was initially not ready to become part of the military to end it. When his father decided that he wanted to send him to West Point in 1839 so that Grant could receive a free education, the 17-year-old rebelled. “But I won’t go,” Grant insisted. His father stood firm, Grant recalled. “He thought I would, and I thought so too, if he did.” Even when he arrived at the military academy, Grant remained unhappy. “A military life had no charms for me,” he insisted.

Grant also harbored anti-military feelings, even when he reentered the army to fight in the Civil War. He was frightened of battle, especially leading men into combat. When Captain Grant took command of the 21st Illinois Infantry in 1861, he once again came face to face with conflict.

“My sensations as we approached what I supposed might be ‘a field of battle’ were anything but agreeable. I had been in all the engagements in Mexico that it was possible for one person to be in; but not in command. If someone else had been colonel and I had been lieutenant-colonel I do not think I would have felt any trepidation…”

After a night of sleep, Grant still did not feel better. He marched his men toward the enemy and “my heart kept getting higher until it felt to me as though it was in my throat. I would have given anything then to have been back in Illinois, but I had not the moral courage to halt and consider what to do; I kept right on.”

When he saw the valley below and saw that the Confederate “troops were gone. My heart resumed its place. It occurred to me at once that [Confederate Missouri State Guard Brig. Gen. Thomas A.] Harris had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him….From that event to the close of the war, I never experienced trepidation upon confronting an enemy, though I always felt more or less anxiety. I never forgot that he has as much reason to fear my forces as I had his. The lesson was valuable.”

Life Partner: Julia Dent married Grant on August 22, 1848. She had a lazy eye, often posed for images in profile to hide it, and recalled that as a child she “used to cry” about her looks. But Ulysses saw nothing but beauty in the woman he loved. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Grant’s admission that he found combat frightening is an important insight into his attitude. Too often, people believe that Civil War officers were fearless supermen, when in reality they were often frightened. And, as Grant indicated in his memoirs, it is also important to remember that command is not an easy task. Grant is often pictured as a butcher, an individual who threw his men into battle casually and needlessly. In fact, he felt, as they did, the fear of combat. War was not a romantic adventure; it was a place of terror, gore, and death.

Yet when he fought Robert E. Lee in Virginia in 1864-65, Grant fought him with all he had. He believed strongly that the only way to defeat the Army of Northern Virginia was to destroy it, to attack all Confederate forces on all fronts at the same time, and to wear away their fighting strength. Other Union generals had tried to outmaneuver Lee and his Confederate army and capture places rather than destroy their armies; they had failed.

Grant began his final campaign on May 3, 1864, in Virginia’s wilderness. He expressed his plans and the results he expected bluntly. “The campaign now begun was destined to result in heavier losses, to both armies, in a given time, than any previously suffered, but the carnage was to be limited to a single year and to accomplish all that had been anticipated or desired at the beginning of that time. We had to have hard fighting to achieve this. The armies had been confronting each other so long, without any decisive result, that they hardly knew which could whip.” As Grant realized, the next year saw desperate fighting, high casualties, but eventual victory for the Union troops.

Grant is often pictured as a butcher, an individual who threw his men into battle casually and needlessly. In fact, he felt, as they did, the fear of combat.

In April 1865, the war came to an end in Virginia with Grant’s all-out warfare wearing Lee’s forces down until the Confederates had insufficient manpower to fight back. After a bloody year, Grant broke through the lines at Petersburg and then pressed on to Richmond. He was clearly in command of the situation. What followed was a series of letters in which Grant called for Lee’s surrender, and Lee tried to delay so he could get the best terms possible. His first letter to Lee on April 7, 1865, was a classic. Grant wrote: “[T]he results of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance….I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the Confederate States army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.”

Us Grant Memoirs By Mark Twain

Despite the hard war that he believed in, Grant made clear in his memoirs that he had a softer side, too. Instead of gloating about the beating he had inflicted on Lee and his army, Grant indicated that “my own feelings, which had been quite jubilant on the receipt of his letter, were sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.”

In the field: Grant studies a map at his headquarters near Cold Harbor, Va., in 1864. He is accompanied by staff members Lt. Col. Theodore Bowers and Chief of Staff John A. Rawlins. (Library of Congress)

Us Grant Memoirs For Sale

Grant also realized the appeal of Abraham Lincoln, the tragedy of his death, and the coming to power of Andrew Johnson. “Mr. Lincoln, I believe, wanted Mr. Davis to escape, because he did not wish to deal with the matter of his punishment….He thought blood enough had already been spilled to atone for our wickedness as a nation….He would have proven the best friend the South could have had, and saved much of the wrangling and bitterness of feeling brought out by reconstruction.”

Us Grant Memoirs

Grant insisted that the “universally kind feeling expressed for me at a time when it was supposed that each day would prove my last, seemed to me the beginning of the answer to ‘Let us have peace.’” And, knowing that he was close to death, Grant completed his memoirs with the words, “I hope the good feeling inaugurated may continue to the end.”

Grant’s memoirs present a great insight into the general and his thinking. There is no better way of understanding this great American than by reading this outstanding self-evaluation, now published with the modern world in mind.

John F. Marszalek is W.L. Giles Distinguished Professor of History Emeritus, and Executive Director and Managing Editor of the Ulysses S. Grant Association’s U.S. Grant Presidential Library at Mississippi State University in Starkville. He led the editing of the most recent edition of Grant’s memoirs, with assistance from editors David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo.